Facing down shop crime

Big Interview with Asian Trader magazine: Nick Fisher, MD Facewatch

After starting his career at the RAC and moving on to Dixons and Phones4U, Nick Fisher has found his vocation in making shops safe for staff again. Here is the story of Facewatch as told to Andy Marino

Facewatch HQ is in London, but when I call Nick Fisher he is at home in Derbyshire, enjoying the countryside despite grey skies, and happy that it’s easy to go for a bike ride any time he wants.

It seems suitable that we are speaking just now. Demonstrations have turned into riots in London and other UK cities, and shop crime in Convenience has almost doubled during lock-down – criminals have found their other stores of choice closed (except to looting), so they descended on local shops instead.

Facewatch, after all, is a gotcha technology that shop thieves and thugs will be powerless against, or at least that’s the theory. I want to know all about it: can retailers at last have access to a powerful tool to fight back against the tide of criminality that seems to be overtaking us – a tide Nick Fisher actually describes as a tsunami?

Nick has been vocal, not least in this magazine, about the need to thwart the rise of crime, but he has decided that the best way he can intervene is to leave the streets to the police.

“The police use facial recognition and there’s been a number of legal cases (all funded and supported by civil liberties groups) where the police have been taken to court for not securing permission or failing to notify – there was an instance in King’s Cross where the Met put up cameras, probably inappropriately, without telling anybody and no signage,” he says.

“The fundamental difference with public CCTV is that Facewatch is private, for businesses,” he says, as we talk about the toppling of statues, “so the rioters are observed by the police and we have nothing to do with that.”

With all this hullabaloo over privacy rights and GDPR, it’s a minefield that he doesn’t want to step into. He sees the police and government suffering terribly from laws and red tape and has found a genius way to stay above the fray.

Private property, says Nick, is fundamentally different from the streets, and the attitude of Facewatch is that when you are in my shop, it’s my rules – and it’s all legal.

“I say to these civil liberty groups, who often seem to want to defend criminals, that I will arrange for you to go and work in a store so you can experience it for yourself and it might change your view, He says, adding that they never take him up on the offer.

The beginning

Nick Fisher CEO Facewatch

“I come from a retailer’s background,” says Nick, who spent 30 years in the industry. “I helped out Carphone Warehouse for six months, because I had the experience of ten years at Dixons, and during that period a friend of mine introduced me to a guy called Simon Gordon who owns Gordon’s Wine Bar.”

Gordon’s is in the passage beside London’s Charing Cross Station that leads down to the Thames Embankment. Its vaulted cellars are evocative and lit with candles. Plenty of city folk and tourists drink there, and so plenty of pickpockets and bag-snatchers would also turn up. Gordon had founded Facewatch because he was sick of the police giving up on crimes that were happening in his bar.

“It started off as a digital crime-reporting platform, a bit like Pubwatch, and he’d been at it for five-plus years. He’d made a lot of progress but wasn’t making any money.”

Nick told him what he was doing was commendable but not commercial. First because he didn’t charge his subscribers enough and second because his principal model was reporting crime to the police, who weren’t interested in those types of crimes because they didn’t have the resources.

“The police are very public about that,” opines Nick. “In the five years since then it’s got even worse and they’ve said they’re not coming out for less than £100 or £200.”

He told Simon that from a retailer’s perspective, what they want is just for the crimes not to happen in their store.

“The challenge with CCTV – and I speak from experience, having run an estate with 700 shops – is that it’s observational technology designed to be mounted in the roof. They have HD recorders because you are supposed to record somebody pinching something and then intervene,” says Nick.

“But if you do, it’s a really complex situation. And if you miss the incident, then notice later on you’ve lost £60-worth of meat and sausages, there’s nothing you can do about it except spool through footage looking for when it happened.”

The step after that is the hardest: to get the law interested. “The police will tell you to burn it on a disk and you’ll never hear from them again.” You’ve wasted an hour of your life and lost £60.

“We needed to come up with something proactive not reactive,” Nick concludes.

The available facial recognition tech was good enough if the subject stared into the camera – as you do at passport control – but wouldn’t help with a hoodie slinking into a store with his head down.

Nick was working on a new kind of digital algorithm that could get past this problem.

“[Gordon] liked my idea and asked me to write a business plan, so I did and we raised a first round of funding to develop the technology and the platform, and examine the lawfulness of holding stored and shared data.”

The next round, which was bigger and successfully completed last October, was to commercialise the product and take it to market: “We raised a substantial amount of money,” says Nick, indicating that investors were impressed.

Since then, the marketing has gotten underway. Facewatch now has agreements with two key distributors, the established CCTV companies Vista and DVS, “So we don’t have to go out and build our own sales force – we now have distribution partners who have their own CCTV installers and massive customer bases, and they take the Facewatch proposition to their client.”

What comes next, the big campaign?

“That’s where we are now, the early days of going live,” says Nick. “We’ve got a number of licences already out there and the amount of interest is incredible. Obviously with retailers having just been through Covid-19, even with customers having to be two metres apart they are still seeing crime at a ridiculous level.”

Watching the Defectives

I ask Nick to explain how it works – not just the technical side but the legal side as well. How are both made criminal-proof?

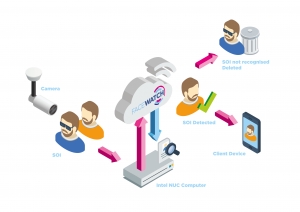

“It’s about identifying individuals,” he answers, “low-level criminals, not murderers and rapists but people who come into your store and just verbally or violently abuse you, and/or steal from the store.” Paradoxically, the every-day nature of most of the crimes – and the fact that it’s on private premises, is the magic that makes Facewatch work.

Nick tells me about his new software – “periocular” software – that can recognise a covered face. “We’ve just developed it, and it will just take sections of the eyes, brows, cheekbones – and it’ll work with hats, sunglasses and masks on.”

The fact that crime is also mostly local can help, too. “If you speak to anyone in retail, anyone in the convenience sector, they’ll know the top five who come into their store and they probably know three of them by name.”

Facewatch is a bit like email, in that it becomes more effective and efficient the more users it has. “So Facewatch will tell you whenever they enter the shop, but it will also help you identify the others, that aren’t regular but do operate within your geographical area.” This means that if a face is on the watch-list of a shop even eight miles away, the first time he enters your store, you will get an alert.

If the thief wraps up carefully it won’t help him if he has been photographed previously or somewhere nearby, says Nick: “The quality of algorithmic technology has gone through the roof in the last couple of years. There’s new releases of software coming out every ten weeks from the developers: it’s pretty advanced stuff now.”

Whether this is allowed all comes down to the legal small-print, which is watertight because Facewatch has gone over it with a fine-tooth comb at the highest levels.

“Part of our licencing contract is signing an information-sharing agreement with Facewatch, and that means we hold the data for the client and become their data controller. This is fantastic for the retailer because it means they don’t have to worry about anything. And then Facewatch shares the data proportionately with other retailers in the area who are Facewatch subscribers,” Nick explains.

“The object of Facewatch is to build this big, powerful database that we hold, store and share on behalf of our clients. We mitigate their risk, we have data-sharing rules, we have the relationship with the ICO [Information Commissioner’s Office] and other required bodies, to own and manage this data on our clients’ behalf.”

And in practice? “If there are three separate retailers on Bromley High Street and they all have Facewatch licences, and have each put ten thieves into the watch-list, they share between them a database of 30 in that area,” says Nick.

Retailers like this because next to crime, their biggest fear – quite correctly – is data. They don’t know whether they should see it, whether they should be sharing it, or whether they should hold it or store it. Biometric data, such as faces, is classed as “special-category data”, and you are not allowed to possess it without explicit permission of the subject.

But Facewatch can.

“An employee might give you permission so he can open the office door but a thief certainly won’t give you permission to put them on a watch list,” Nick says. “And there’s a set of rules around GDPR and the proportionality of sharing data you have to satisfy to hold on to stuff. We take care of that.”

He says Facewatch has worked with the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice, the Joint Security and Resilience Centre (JSaRC) and the ICO, to make sure they are doing everything above board.

“We’ve had our GDPR information-sharing-DPA [Data Protection Act] compliance all signed off by the leading QC on cyber law in the UK, Dean Armstrong [of the 36 Group]. He marked our homework, so to speak. We’ve ticked all the right boxes and we are super-transparent in everything we do.”

It sounds as if the criminals’ biggest nightmare is about to become real. Rights are still protected, and you can ask Facewatch whether you are on the watch-list and they have to tell you – but if a thief wants to be removed from it, he would have to come up with better evidence than what is stored on the database.

“If that thief does a personal access request we can tell the day, date, time and camera number and the individual who put that report on the watch-list,” laughs Nick. “And then we’ll use the evidence to challenge the request to be removed from the list: We have evidence of you right here stealing £60 of meat and sausages on such a date, and if you want to contest it, go to the police and we can have a discussion about it.”

At the same time, the innocent have nothing to fear – and for once, it’s true. “You as an individual can do as subject-access request to Facewatch any time you want,” says Nick. “We’ve only had two requests at Gordon’s Wine Bar, and funnily enough they tend to be from older blokes who have been there with younger ladies!”

In reality, a person would only ever be on the watch-list if they had committed a crime or an assault, because it is illegal to store just any old data. Most gets immediately deleted.

Putting it into practice

It strikes me that the genius part of the Facewatch offer is not the tech, even though it is cutting-edge. As Nick says, many companies can offer the hardware needed to take good pictures of ugly mugs.

Rather, it is the legal and data ju-jitsu that Facewatch has accomplished that is key. It seems to have managed cut through the tangle of permissions and loop-holes exploited by criminals and their professional helpers to thwart traders and owners.

“All biometric companies in the UK sell the tech, but Facewatch are essentially selling you the data management service,” says Nick. “The tech is included, of course, because the tech sends the alert but the difference is this: If I, as a tech company, were to sell you a facial recognition system then I don’t want to look after the data. I just want you to buy the tech from me. The problem with that is, you can only use that tech legally with the permission of the people you want to put on the database. That works fine with membership stuff like gyms, where you look into a camera for admittance, for example. But every member has to consent to supply a picture of their face for comparison. The data would be held by that gym, that business. But they can’t use the data for anything else, such as crime prevention, because permission hasn’t been given by the individual for that.”

That’s the reason shop crime until now has been rampant: every incident has to be dealt with as a new thing rather than spotted and avoided at the outset. It is slow and inefficient and soul-destroying. There has been no legal means of automating pre-emptive detection – until now.

There are three rules of using facial recognition, Nick explains. One is necessity – you need to demonstrate your need for it. You can’t just collect it if you haven’t any crimes. Second, you have to be able to show it’s for crime prevention purposes if you are not getting permission to collect images from the people whose pictures you are taking. Third and most important, you can only hold that data if it is in “the substantial public interest” – so a business can’t do it just for themselves as that is not a substantial public interest.

“But Facewatch is an aggregator of information across businesses and geographic areas which acts as a crime prevention service and we share it in the public interest,” Nick says. “So you need to be a data aggregator, but a camera company can’t be that. Likewise a facial recognition software company can’t be a data aggregator because each company would have a different algorithm and database.”

But Facewatch sits right in the middle. “You just have to make sure all roads lead to Facewatch because that’s how the data becomes lawful to use.”

Big Brother is kept in his cage: there won’t be any nationwide watch-list. Proportionality rules keep it local – a database in London would have a radius of about five miles, but maybe 30 miles in Norfolk. “Guys who go into your readers’ stores and nick booze, deodorant, cheese and meat – they don’t travel more than five miles,” Nick confides. “They only start to travel when you start dispersing them. We put facial recognition into every store in Portsmouth and all the thieves went to Southampton – or to Tesco!”

I want it now!

“You could put it up pretty much instantly,” Nick explains when I ask exactly what a retailer would need to do to have Facewatch installed.

“They could either phone us or one of our distribution partners. The distribution partner would then introduce them to one of their re-sellers or installers who would then make an appointment with the retailer to see the site. They’ve got all the tools with them – you have to install the camera on a certain angle, at a certain pitch. It tells them what camera they need and measures the distance. It’s really simple and for a CCTV installer it’s a doddle of a job.”

Facewatch is sold on a per-camera, per-licence basis of £2,400 per annum, £200 a month essentially, which includes all the hardware and licencing and all the sharing of data – everything they’ll need other than the installation and the camera itself. “A lot of retailers already have their preferred installer,” says Nick. “He has to be accredited by Facewatch, and if not, we’ll train him, and if a retailer has no installer, we’ll recommend one.”

It’s pretty straightforward, he adds. “In the same way as they would add more CCTV cameras to their store. Cameras are cheap, £150 or whatever. A standard HD camera is fine. It’s got to be of a certain lens-type and we’ve got an offer at the moment where the camera is free.”

The proposition is that with the average store leaking thousands of pounds a year in theft, Facewatch will easily pay for itself. “Everywhere we have deployed facial recognition, in the first 90 days, from a standing start, even without an initial watch-list, we have seen a greater-than 25 per cent reduction in crime with every deployment,” says Nick.

He adds that it even works with repeat offenders that you might not have put on the watch-list, because the thief is known by some other shop participating in Facewatch and they would see the sign in your window, effectively warning them off.

“We’ve even got a little [digital] tool that we give to our installers, and it works out the ROI,” Nick tells me. “So any store that loses more than £8,000 per year – which is at least half of them – will have an ROI in as little as 11 months, your money back inside a year. I’m just talking about the savings against crime, that’s not to mention all the time you would have had to commit preparing evidence to give the police, and all the hassle and stress you avoid, and managing the emotions of your employees who have been abused or assaulted.”

I ask Nick for his message to the nation’s retailers.

“I can say this,” he answers. “I am not some bystander in an ivory tower who just has a viewpoint. I’ve been a retailer for nearly 30 years. What typically happens in a recession is that money gets tight and crime goes up. What we are about to see is incredible.

“The police are saying they just can’t spare the time to deal with it. That whole, ‘Your problem, not ours’ approach is going to be significantly worse after Covid-19 than before, and it was bad enough then. Facewatch is a really simple deterrent proposition and it’s easy to install. We look after all the data on behalf of our clients – there is a tsunami of crime coming our way.”

Facewatch

Facewatch